[this piece was originally published in LinkedIn Pulse]

In 2008, I opened up a coaching practice, working with women who wanted to make a change in their careers. Some aimed to transition into more fulfilling work. Others wanted to advance within their current industry. Others wanted support as they launched new businesses.

I was always impressed by my clients. They were talented, hardworking, high-integrity people – the kind of team members any organization would want. Yet I started to notice something odd: these women often didn’t see their own capability. They didn’t see themselves as ready for that next professional step or as worthy of a seat at the most important tables in their organizations. I kept running into brilliant women who couldn’t see their own brilliance.

There are now a handful of books and numerous articles on this topic of women’s self-doubt. Most point out what seems to be a troubling pattern of women underestimating themselves, and then urge women to become more confident.

After several years of helping women have careers they desire, I think that’s entirely the wrong idea. And I believe that one of the most important truths about women and confidence is still missing from our conversation.

It’s this: self-doubt is indeed part of the problem. It is part of what holds talented women—and talented men for that matter—back. But contrary to what we’d expect, confidence is notthe solution. The solution is having a new relationship to one’s own self-doubt.

Twyla Tharp is one of the most renowned choreographers of our time. She’s won a Tony Award, two Emmy Awards, and holds nineteen honorary doctorates. She has every reason to be confident. Yet she writes about the fears that still come up for her, all the time in her work: “People will laugh at me.” “I have nothing to say.” “Someone has done it before.” [1]

Acclaimed, best-selling author Dani Shapiro has shared, “I was looking at my computer one day at my list of everything I had written in the last few years…I realized that every single one of these pieces had begun with the words running through my mind, ‘Here goes nothing…it’s not going to work this time…I’m in over my head…I’m not going to be able to figure it out.’” [2]

And Cherry Murray, dean of the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, who has published more than 70 papers in peer-reviewed journals and holds two patents says, “Do I ever think I’m not qualified? All the time.” [3]

What has enabled women like Twyla Tharp, Dani Shapiro, Cherry Murray and countless others to lead and create, in spite of insecurity? Dani Shapiro recounts, “I’ve had this practice for so many years now of hearing that voice say, ‘You can’t do this,’ and not listening to that voice.” And as Twyla Tharp says of her fears, “If I let them, they’ll shut down my impulses…and perhaps turn off the spigots of creativity altogether.” It’s not confidence that enables these women to succeed, but the way they relate to their self-doubt.

Most of us haven’t gotten the memo on this important distinction. According to a recent survey of 200 professional women that I conducted, 85% of us believe that we’d be more successful in careers if we were more confident. 60% of us believe that greater confidence is one of the top two changes that would most enhance our career success, more than a better team, additional training or knowledge, or more time for our work—second only to finding a great mentor. In other words, most of us assume confidence is a critical element for our career success.

But when we believe we need to have more confidence to be successful or to pursue our aspirations, we tend to give ourselves a very difficult—if not impossible—task: the task of becoming more confident. We put important career stretches and risks on hold as we wait on what we perceive as needed confidence.

If someone believes, by contrast, that people having their careers of their dreams grapple with consistent self-doubt; if they believe they don’t need any more confidence than they have right now in order to accomplish their most important goals; if they shift their vision of their ideal self from a confident rock star to a-wracked-with-self-doubt rock star, they have a path forward from where they currently stand.

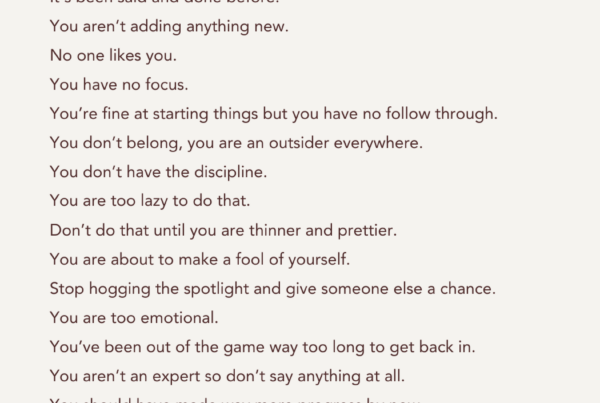

In practical terms, this new way of relating to self-doubt is very simple. It’s not about arguing back with the inner critic voice, or getting angry at it; both of those prove counterproductive. Rather, we each need to recognize the voice of the inner critic when it speaks (some clues: it is usually harsh, repetitive, anxious) and differentiate that voice from the voice of our own best thinking. For many of us, the inner critic’s rants have become like water we swim in; we’re so used to its voice, we no longer hear it. We need to learn to notice it and identify it. This means simply having the thought, “Oh, I’m hearing my inner critic right now,” when it speaks. In that simple recognition, we become an observer of its voice, and we then have a choice about how to respond to it.

Second, once we identify it, we need to remember what it is. The inner critic is usually our fear of failure, change, or visibility using a very sophisticated strategy of attacking us, in an attempt to get us to shrink right back into our comfort zones. It’s our safety instinct dressed up in a fancy costume.

This is why we tend to hear the inner critic most vocally when we are taking important leaps forward or pursuing our most deeply held aspirations. The inner critic is like a guard at the edge of our comfort zones. When we are safe within the familiar zone of the status quo, the guard can sleep. As we approach the edge, it wakes up, and it will tell us any lie it needs to in order to get us to move back into territory that keeps us safe from possible painful criticism, failure, or vulnerability.

When you remember all that, you can do the strange thing of remembering that your inner critic is probably not telling the truth, even as another part of you feels sure its words are true. You can speak up despite the inner voice saying your idea is ridiculous. You can launch the business despite the inner voice saying you aren’t CEO material. You can apply for the stretch job despite the inner voice saying they’d never consider you for it. And the more you practice it, the more it can become a habit to do so, as it is for women like Dani Shapiro and Twyla Tharp.

When I asked survey respondents what they thought would most help their career success, they responded with something quite intriguing. Many replied that “more courage” was the thing that would most boost their career success. “More courage” was a more common answer to that question than more time for work, a better team, or more knowledge and training.

Confidence is faith in our abilities and ourselves. Courage is going forward even when we don’t feel that faith. We talk a lot to women about their finding more confidence, but it’s time we put more attention on courage, on taking action in the absence of certainty that we can do a task well. Women today are forging new ground, without many role models, and with a powerful legacy of centuries of women’s exclusion from professional life, a legacy that persists both within us and around us. Confidence likely won’t always be with us as we forge new paths. But we don’t need confidence to do what we most want to do in our careers. We need to learn to take action in the midst of self-doubt, and we can each begin practicing that today.

[1] Twyla Tharp quote from The Creative Habit: Learn It and Use It for Life. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), 21.

[2] Dani Shapiro quote from “The Creative Descent of the Shero.” En*theos presents: Shero School for Revolutionaries with Jennifer Louden. 23-28 September 2013.

[3] Cherry Murray quote from “Unmasking the Impostor,” Nature (459) 2009, 468-469.

photo credit: Himanshu Singh Gurjar