You can listen to this exercise in audio, too. Press play below or download as an MP3 here.

Recently, in a workshop, one of the participants asked me, “What if I’m not sure I’m good enough at my work to go for that bigger stage? What if maybe I’m not ready yet?”

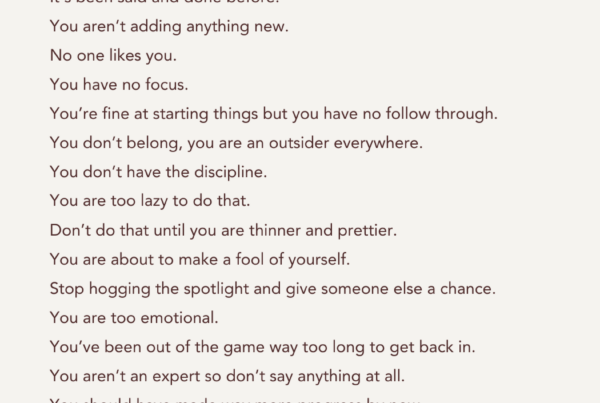

These kinds of questions, “What if I’m not good enough?” “Am I good at this particular thing, or that?” “Do I have anything unique to say?” are all of a category.

They are self-assessment questions – questions in which we try to look at ourselves as if from a distance, and judge how talented, ready, qualified, we are.

What I replied back to her is a principle I’ve arrived at slowly, over years of talking with women about their dreams, longings, and subtle ways of holding back.

We do not need to ask self-assessment questions.

We do not need them. We can drop them entirely, and then walk right into the open, warm space that is waiting for us, once we’ve put them down.

Self-assessment questions seem to protect us from failure or embarrassment, but they mostly cut us off from possibilities for growth and success.

They masquerade as the kind of questions realistic grownups ask, but they are in fact the kind of questions a frightened ego ruminates upon.

Imagine a young girl – maybe age 4 or 5 – who decides to build a fort. She’s very unlikely to worry that she’s not up to the task, or to fret that no one will like her fort. And yet…and this is so important: she also has a way of assessing and improving her creation.

Along the way in making it, she naturally will periodically ask herself,

“What does it need now? More height? More pillows? A sturdier entrance?”

Here she’s practicing a creative discernment of editing and adjusting her work.

Sometimes her “what do I want to add?” questions lead her to realize she needs outside help.

“I need mom to get more pillows down from the high shelf in the closet.” “I want my friend to bring over flowers to decorate the fort with.”

Here she’s asking questions of creative discernment that have to do with collaboration, resources, and team.

And of course, from time to time she asks herself,

“Is it done?”

This is the question of completion that every creator must ask and respond to.

Now, notice the questions she would not ask herself while fort-building (unless some adult or kid had already intervened in her creative life and trained her to do so).

- She would not assess whether she was “a good fort-maker” in some absolute sense. It would not even occur to her that there is such a thing.

- She would not ask whether she deserved to make forts, to take up the space and hold the creative authority of fort-making.

- She would not worry about whether she was prepared enough to make a fort.

- She would not ask, or care, whether her fort was going to be “unique” relative to others.

- And although she might be excited to share her fort, she would not ruminate about what might happen if other people didn’t like her fort much. She’s focused on how she’s in love with her fort.

Here’s the pattern: She asks questions that help her assess the work – but she is not assessing herself. Here’s that crucial difference:

Can we be more like this girl?

Can we work, create, express ourselves in the vein of her work/play?

Okay, I hear some of you asking,

“But this girl is just doing this for fun. What if this is my work and I’m not getting results – an audience, or a thriving business?”

Even if that’s your situation, I still 100% stand by my recommendation that you drop all self-assessment questions. If you need questions to ask yourself, ask the creative discernment ones instead: Is your work authentic? Are there areas you might need outside help and collaborators? If you aren’t getting traction/audience/business in your work and you want to, you may also need to gather more information from your audience/customers about what’s working for them (and we’ll talk about that in the next post), but you do not need self-assessment questions!

Self-Assessment and Ego

The ego loves self-assessment. As psychologist Dr. Nicole LePera has written, the ego is “how you see yourself. It is the part of your mind that identifies with traits, beliefs, and habits.” Being in ego is about being focused on our story about ourselves, rather than our more flexible, fluid, felt experience.

The ego is always grasping for a story about the self to help it feel safe and orient in a vast and uncertain world.

That story might be, “I’m a nice person, I’m an American, I’m a hard worker, I’m bad at details,” and a host of other attributes.

Fascinatingly, the ego feels in control whether that story is a self-confident one or a self-critical one. It just likes its familiar story.

The collective ego in our culture has developed workplace, religious and educational systems that help to feed every person an ego story just for them. We learn from these systems, “I’m good at math.” “I’m not an athlete.” “I’m a good person.” “I’m a bad kid.” “I’m a caretaker.” “I’m a provider.” “I’d be good at this kind of job, but not that.”

One problem with ego stories, with self-concepts is that they are usually false and reductive, and therefore limiting and misleading. We are all more complex and changing that our ego stories leave room for.

Here are some of the forces that cause our ego stories to be way out of touch with reality – compelling fictions, but not fact:

- Early childhood messages & others’ projections. In our early lives, when we’re most vulnerable to others’ ideas, we receive messages from parents and teachers about what we’re good and bad at, about what kind of life or career we deserve. We might hold the concept of “I’m the smartest girl in the class” because that’s what that high pressure parent told us, or we might hold the idea “I’m not really a leader” because our big brother always took on the leadership roles.

- Internalized negative stereotypes. “I’m not good at math.” “My ideas don’t make sense.” “I’m not the academic type.” These self-concepts often feel personal to the individual holding them, but in fact often are internalized versions of gender and racial stereotypes from the culture.

- Past painful moments. Have you noticed that a single, hurtful piece of critical feedback still impacts how you see yourself in some regard? Human brains are wired to have what psychologists call a “negativity bias” – we remember and weigh negative experiences more than pleasurable or neutral ones. When we self-assess, we remember any painful experiences (like that one excruciating feedback comment from ten years ago)…even as we ignore all positive feedback on the same quality or skill.

- And perhaps most of all, fear. Playing bigger is scary – especially for the part of us that likes familiarity, emotional comfort, and blending in with the crowd. When we ask “Am I ready?” or “Am I good enough?” often, we’re scared and subconsciously looking for a way to retreat back into a comfort zone. Self-assessment questions offer a kind of cloak for fear to hide under.

With early childhood messages, stereotypes, negativity bias and fear each distorting our self-perception, how accurate can our self-assessments be?

So that’s one problem – ego stories are always blind to some truths and incorporating of some falsities. But the deeper problem is that living in our ego story is a very suffering-inducing way to live. It feels constraining, defended, and disconnecting from others, because it is.

Shifting Our Questions

So here’s the thing, and this so surprised me when I first recognized it: when we are obsessing over our lack of qualifications and our possible failures, when we are in self-doubt, we are actually wrapped up in our egos! We are thinking about ourselves, rather than the work itself, or the people we want to serve.

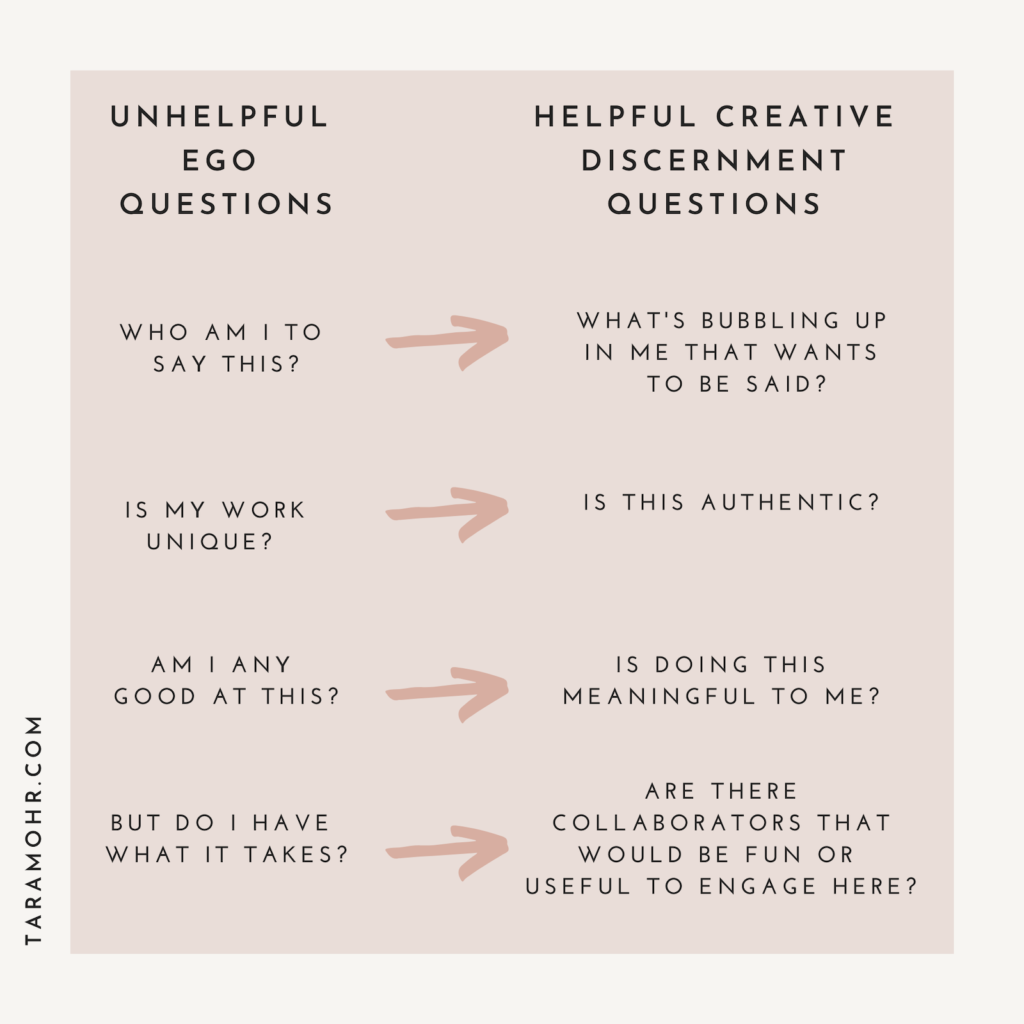

We can see this clearly in the contrast between two questions we might ask ourselves.

Self-Assessment Question: “Who am I to say this?”

vs

Creative Discernment Question: “Is there something bubbling up in me that wants to be said?”

In the first question, we go into that egoic mode of trying to assess and judge ourselves from the outside. We are thinking about ourselves, our reputation, our potential pain or embarrassment.

In the second question, we are inquiring into our own inward, felt experience. And in the second question, we aren’t so self-focused, so we have room to honor the spirit, the “genius” as Liz Gilbert would put it, of our ideas, of what wants to be expressed.

So today, I want to invite you to notice your self-assessment thoughts, and decide not to follow them. Choose to dismiss your self-assessment questions. Simmer in your creative discernment questions instead.

It’s worth noticing that self-assessment questions are not to be confused with useful, personal reflection questions, in which we check in with ourselves in order to shift or address what needs attention in us. Questions like, “Am I fearful today? Am I resentful? How can I be of service to someone?” are great. Questions like, “Where am I doing harm in my life and how can I change that?” are great. But you’ll notice these questions don’t have us looking at ourselves from the outside as a package and judging how we measure up relative to others, or in some absolute sense. That’s where we get into trouble.

If we want more creativity, joy and freedom in our work and creative lives, this is what we need to move toward, choice by choice: away from ego stories, assessments of ourselves, and back to the landscape of emotions, sensations, ideas, inspirations, conscience – our inner lives.

I’m providing a handy printable for you of the unhelpful self-assessment questions we so often ask, and the more helpful, creative discernment questions to replace them with. You can grab that here so you can keep it handy – and please share with a friend who could use these, too.

xoxo

Tara

Top photo by Daniele Levis Pelusi